Dr Jon Lewis is our Chief Strategy Officer. His background spans technology innovation and product delivery across a wide set of industries from mobile communications to healthcare. At Telensa Jon has pioneered several smart city applications, including smart parking and smart waste management. More recently he has led the Urban Data Project - a new approach to the collection and responsible use of data by cities, transforming trust and privacy using artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Dr Jon Lewis is our Chief Strategy Officer. His background spans technology innovation and product delivery across a wide set of industries from mobile communications to healthcare. At Telensa Jon has pioneered several smart city applications, including smart parking and smart waste management. More recently he has led the Urban Data Project - a new approach to the collection and responsible use of data by cities, transforming trust and privacy using artificial intelligence and machine learning.1. No two cities are the same - so it is difficult for a city to predict what its smart city infrastructure needs to look like in the future. As such cities need open technologies. Open technologies create data interoperability that is crucial to accommodate new developments in sensors and network connectivity. Without open technologies, cities could be faced with a limited proprietary ecosystem, stunting their options for a smarter city.

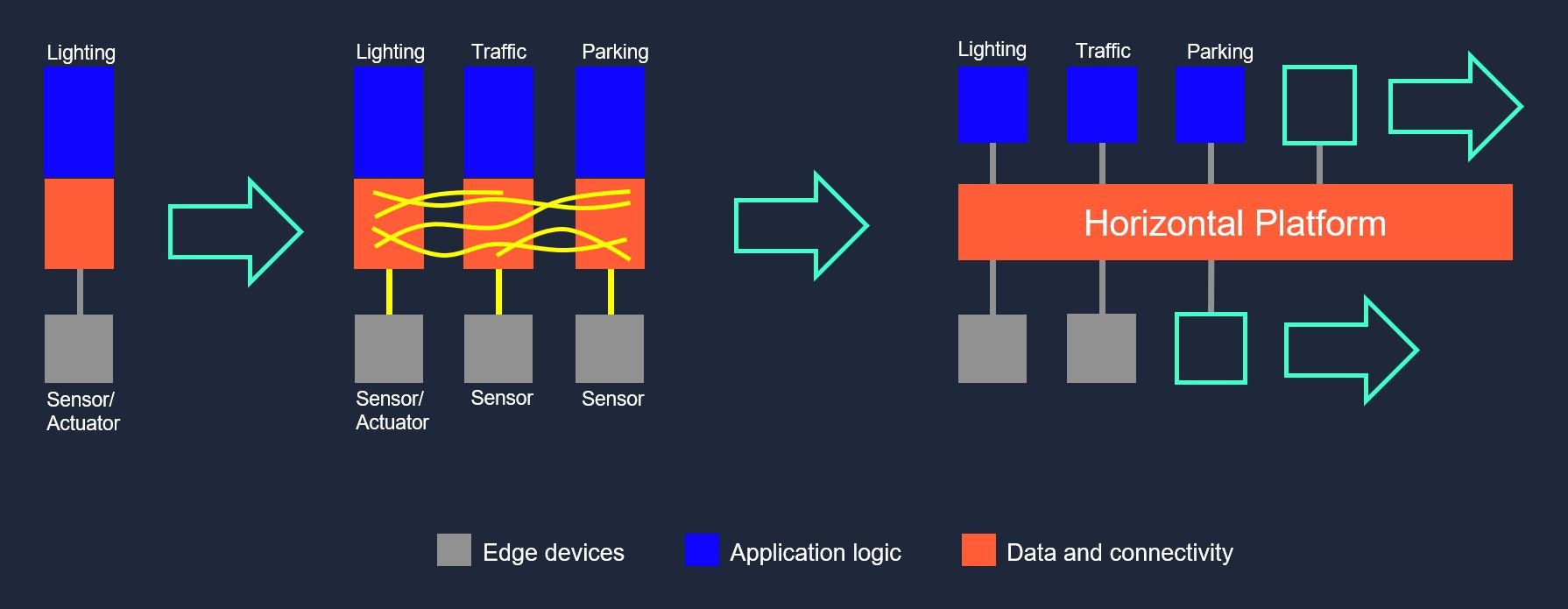

2. Horizontal Platforms - cities today typically run vertically integrated applications, efficiently designed for specific functions, like streetlight control, but this is beginning to change.

Custom integration is required to enable these systems to work together and share data, and these integration costs multiply as more city functions are digitised. As cities put together their own selection of solutions, no two cities will be built in the same way. This makes it hard to get common data sets and cities remain walled gardens due to the inability to share and standardise.

So for all cities to benefit they need applications that snap into horizontal data platforms that can be used at a national level. Using a horizontal platform generates multiple end use cases that can be achieved in a more efficient way and creates better interoperability between departments and cities themselves.

Example of the move from vertical applications to a horizontal platform:

3. Siloed ways of working not only exist between cities, they also exist internally between city departments. Even cities that work well between departments will have challenges with historical processes, internal politics and limited control and influence. In reality a city is a combination of all its enterprises, all its associations, charities groups, schools and everything else. So how can cities co-ordinate all of these enterprises so they’re not siloed? If you just concentrate on the city itself and what it can control, there are a number of different approaches the city can take:

- Bottom-up – individual departments make decisions about how they can improve their own operations. This is partly why smart street lighting is so successful: the application has a business case but also, there is a well-defined customer and operational entity that gets the benefits that smart street lighting provides.

- Top-down – a cross-departmental approach - for example, if a city is digging up the road, all departments will be informed so they can share equipment and costs to be more efficient. However, there is a danger of creating short-term disturbance, decreasing the efficiency of individual departments. With cities strapped for cash, making these strategic investments and potentially taking a short-term hit is not easy to do.

- Assigning a Chief Data Officer (CDO) to set the standard for city digitisation. With appropriate political backing a CDO can break down department silos. Chief Data Officers can have great influence on the IT infrastructure, such as moving systems to a particular data lake or a particular framework – Azure/AWS etc. This is where innovative companies can help reduce silos and future-proof operations, so rather than selling into a single domain they take a high-level, holistic view and take data from multiple sources and these insights can be used across departments.

Overall, cities' current business models create barriers to smart city development. Engaging a CDO that can create an ecosystem of partners, working on a horizontal platform is a good first step! Look out for my blog series to learn more about approach, privacy and trust. Sign up for notifications here:

Topics: Smart cities, IoT, open technology, futureproof, smartcitystrategy